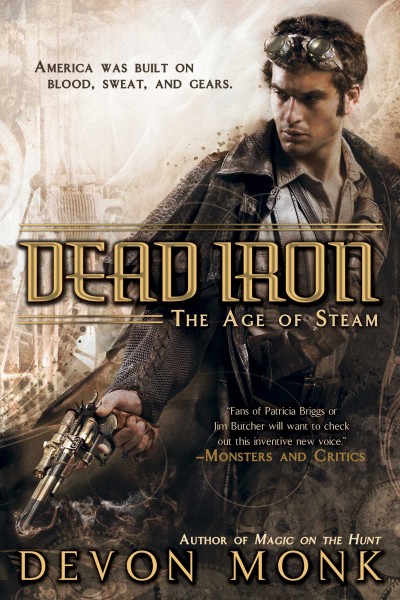

Dead Iron Excerpt

Excerpt

DEAD IRON

Book One – Age of Steam

Cedar had stared straight into the killing eyes of rabid wolves, hungry bears, and charging bull elk, but Mrs. Horace Small had them all topped.

With dirt brown hair piled in a messy bun on the back of her head, and a pinch of anger between her brows, the storekeeper’s wife always seemed half a tick from blowing a spring.

“Two dollars,” she repeated, her fist stuck wrist-deep in the fabric at her hip, her jaw jutted out like a bass on a hook.

“Cornmeal, coffee, and a bit of cheese,” Cedar said mildly. He knew better than to let his anger show, especially this close to the full moon, in a store full of townsfolk eager to get their hands on the fresh supplies and gears from the old states. “Might be I’m missing something.” He looked back down at the receipt with Mrs. Small’s tight penmanship. “How again do they add to two dollars?”

He knew math—knew it very well. He’d spent four years back east in the universities and had plans of a teaching life. History and the gentle arts, not the wild metal and steam sciences of the devisers. He’d done his share of tinkering—had a knack for it—but not the restless drive of a true deviser who couldn’t be left in a room with a bit of rope, metal, and a hammer without putting them all together into some kind of engine or contraption.

No, his needs had been simple: a teacher’s life filled with a wife and a daughter, and his brother, Wil. But that life had been emptied out and scraped clean six years ago, when he’d been only twenty-two. Leaving him a changed man.

Leaving him a cursed man.

“It’s written plain enough,” she said. “You do read, Mr. Hunt?”

“The part there that says ‘fee,’” Cedar asked without looking up. “What fee is that?”

“The rail takes its due. You aren’t part of the railroad, Mr. Hunt. Not a farmer, miner, rancher, or deviser. Not a member of this good community. I’ve never seen you in church. Not one single Sunday the last two years. That fee for the rail is less than all those months’ dues you owe to God.”

“Didn’t know the collection plate took hold to my provisions,” he said with a little more irritation than he’d intended, “and I don’t recall offering my wages to the rail.”

The mood in the general store shifted. The men in the shop—the three Madder brothers, dark haired, dark eyed, all of them short, bull-shouldered, and strong—were listening in. They’d stopped pawing and chuckling at the new metals and bits in the straw-padded crates, and were waiting. Waiting for him to say the wrong thing. Waiting for a fight.

Rose, Mrs. Small’s seventeen-year-old adopted daughter, stepped down off the stool where she’d been dusting. She darted behind Cedar and out the door, silent as a mouse fleeing danger. She had good instincts. He’d always admired that in her.

Mrs. Small lowered her voice and leaned over the counter between them. “You are a dirty drifter, Mr. Hunt. Any man out this far west with no plan of settling down isn’t drifting toward something—he’s trying too hard to drift away from something. The good folk of this town want you to be moving on. You’ve brought enough bad luck down on us. First the Haney stock got drug away by wolves. Then the little Gregor boy goes missing. Trouble like you needs to be moving on your way.”

“Trouble like me?” He tipped his hat down just a bit. “No offense, ma’am, but I took care of the wolf before the Haneys lost the rest of their stock. If I recall, there wasn’t another man out tracking it. And if I’d known about the Gregor boy wandering off, I would have been looking for him too. Animals aren’t the only thing I am capable of hunting.”

This time he did look up. Met her eyes. Watched the fire of her indignation go to ash. It never took much, no more than a glimpse of the thing that lived just beneath his civilized exterior, to end a conversation.

Days like this, he liked it. Liked what his gaze could do. But it was easy to lose grip, to go from staring a person down to waking up with a dead body at his feet. He didn’t want that to happen. Not today.

Not ever again.

Cedar blinked, breaking eye contact with Mrs. Small. He pushed the bloody memories away and gave her a moment, because he knew she’d need one.

He took a moment too. He meant it when he said he’d look for the boy, would have been looking at the first sign of him getting lost. But Hallelujah wasn’t made of trusting folk. They’d seen too much hardship to think a man who kept to himself, and only rarely came to town, would go out of his way to do them any good.

Except for the dandy rail man, Mr. Shard LeFel. Rumor had it all the town held him in high esteem. Rumor had it, when he or his man Mr. Shunt walked by, folk fought a powerful need to bow down on their knees.

Cedar hadn’t yet met a man he’d be willing to bow to.

The Madder brothers swaggered up, caulk boots hollow on the shiplap floor. The brothers worked the silver mine. Breaking rock all day never seemed to satisfy their need to bust their way through a man’s bones every time they crawled out of the hills.

“How I see it,” Cedar said, hitching his words down low, quiet, “I’ve been some benefit to this town, me and my drifter ways. Hunted wolves, mountain lions, and nuisances for ranchers and working folk alike. I’ll be hunting for the lost boy. You can tell the Gregors that when they next stop in.”

He dug in his pocket and pulled out a silver dollar and enough copper to settle the bill. Fee included. He placed the coins on the counter, plus a penny extra, and plucked a jar of ink from the shelf.

Mrs. Small raised one eyebrow, but said no more.

The silver filigreed bird perched on the edge of the high window sang one sweet chirp. Its head was the size of a child’s thimble. The gears and burner inside it were so tiny, it chirped once every hour and needed half a dropper of water a day to power it.

Valuable, that whimsy. He wondered where she had come by it. That delicate of a matic, a fine thing of little practical use, never survived this far west for long.

Beautiful things got crushed to dust out in these wilds.

Outside, the steam clock blew the pattern for ten o’clock. Town was mighty proud of that whistle. The blacksmith, Mr. Gregor, had put it in place of a clock tower right over his shop at the north end of town. Not half again as nice as the steam bells back east, it was still Hallelujah’s pride and joy and could be heard clear on the other side of Powder Keg Bluff.

“Is Mr. Hunt troubling you, ma’am?” Cadoc, the shortest and widest of the Madder brothers, asked.

Cedar picked up the flour with the two smaller bundles stacked on top. He tucked the ink in his pocket and nodded at the brothers, who all wore overalls, tool belts, and long coats loose enough to cover whatever it was they kept stuffed in their pockets. “Just a discussion of good citizenship is all, gentlemen,” he said. “Afternoon.”

He headed out onto the stretch of porch that gave shade in the summer, and the chance of shelter against rain and snow in the other seasons.

The Small Mercantile and Groceries was set on the corner of Main Street—the only street with real gas lamps in the town. The other buildings, thirty or so of them with pitched roofs and walls of milled or plank wood, were laid out in neat rows following the curve of the Grande Ronde River north.

A bustle of people were on the streets this morning, come into town for the new shipment, to pick up mail or trade harvest goods to settle their bills. It brought back his memories of the big cities, though there were more steam matics trundling about in the East. Horses, carriages, wagons, and folk on foot added to the clatter of the place, added to the living of the place, and reminded Cedar of things long lost.

Even the ringing of a hammer on wood reminded him of the civilized life that was once his.

He glanced up the street. His gaze skipped the bakery, butcher shop, tannery, and mill, drawn, as it was always drawn, to the clock whistle atop a turret made of iron and wood and tin, sticking up like a backbone above the blacksmith’s shop. A coil of copper tubes wrapped through the structure and supported a line of twelve glass jugs, round as pearls and big as butter churns. Water poured from the top of the tower downward, like sand in an hourglass, filled the glass jugs one at a time, until they spilled over into the next and turned the gears inside the tower toward the next hour.

Town needed a thing to be proud of. Needed a thing more than wool and timber and silver to keep it alive. Needed something beautiful. Needed hope.

Cedar looked past the tower to the mountains that cupped the valley, two ranges of snow and hardship, blocking Hallelujah from easier lands and the great Columbia River. He knew there was ground enough between the town and the rise of the Wallowa Mountains, an airship could land and lash, but he had never once seen a ship venture over these mountain ranges—not even to deliver supplies or drop mail.

Hallelujah was in dire risk of being forgotten by the world that traveled easier roads to brighter skies.

A song piped out from near his elbow, soft and breathy. Cedar looked down.

Rose was on the porch, her back pressed tight against the clapboard siding, one toe of her boot propped on the lower rung of the whitewashed railing. She was talking to herself, or maybe singing, her head bent, amber hair beneath her bonnet catching the gold out of the sunlight and falling in a loose braid over one shoulder, hiding much of her profile from him.

Around her neck was a little locket the size and shape of a robin’s egg. It looked made of gold and silver, though it might just be the shine of the morning sun upon it. He’d never seen her without that locket around her neck.

She balanced a small wooden plate with gears set flat atop it on the palm and fingers of her left hand. A tiny tin top with a copper steam valve followed the spokes of the wooden gears and gave off a sour little song that changed with its speed as it followed the height and width of each cog. Rose pulled a gear off the plate and replaced it with another from her apron pocket, sweetening the song, all the while talking, talking.

Clever, that.

He’d bet she fashioned it herself. She had the look of the deviser’s knack—a quick mind that trawled the edge of madness, and clever, busy fingers. She had practical smarts too, though, like knowing how to stay away from the back of her mama’s hand.

“Reckon I put your mama in a sour mood, asking her about the Gregor boy,” he said. “I don’t suppose you’ve heard when he got himself lost?”

“Last night is all,” she said, stopping the top with her finger and slipping it into her apron pocket. “Didn’t run off, I heard.”

“Didn’t run? Think he flew out the window?”

She tipped a glance out from behind the brim of her bonnet. Those eyes were blue and soft and wide as the sea. She smiled, the corners of her mouth tucking dimples into her tanned cheeks. Folk around town had their opinions of the girl abandoned when she was a babe. Thought she had too many wild ideas spinning through her head as was proper for a woman. He’d never seen her be anything but kind and steady in the years he’d been here. Deviser or not, madness or not, she had a good heart, that was certain.

Didn’t seem the other men in town thought the same. A woman her age and unmarried was almost an unheard-of circumstance.

“No, Mr. Hunt,” she said. “I think he got took.”

“Took? That what his folks are saying?”

She shrugged.

“They saying what took him?” There wasn’t a night predator brash enough to cross a closed door, and there wasn’t a soul foolish enough to go without a lock or brace in these parts. Maybe the boy wandered when he should have been sleeping.

“Said it was the man.”

“What man?”

“The bogeyman.”

Cedar blinked and went very still. She wasn’t lying. That was clear from the curiosity in her eyes. She’d heard someone say that, someone who meant it. He just hoped whoever had said it didn’t know what they were talking about.

Under his sudden silence, Rose clutched the wooden gear plate tighter and pulled her braid back so it fell square between her shoulders. She did not look away, but lifted her chin and studied his face, his eyes, the angle of his shoulders, his clenched fists. She weighed and measured his mood as if he were made of parts and the whole, more curious than cautious, though she rocked up on the balls of her feet, ready to bolt if need be.

And for good reason. He’d been staring at her. He knew what she saw in his gaze. Knew the beast that twisted inside him. He looked away.

“Mr. Hunt?” she asked. “Are you not well?”

Like he said, she had good instincts. Cedar found a smile and gentle tone left over from better days.

“Well enough. Thank you for your time, Miss Small.”

“Do you think it was?” she asked. “The bogeyman?”

“I think a lady like you shouldn’t need to fret about the bogeyman.”

She did not smile. “They say he came in the night,” she said. “Slick as a shadow. Took Elbert from his bed. Didn’t even leave a wrinkle in the sheets. No one saw him. No one heard him. No one stopped him. Not even his daddy. It’s unnatural.” She nodded and looked him straight in the eyes. “Strange. I think that might be worth a fret or two, don’t you?”

Mr. Gregor was a big man. A strong man with hair and beard as red and wild as the fire he toiled over. Probably looked like a giant from the eyes of a girl growing up in this town.

A crash from inside clattered out; then Mrs. Small’s holler drifted through the doors. Rose flinched, tucked back down into herself, her hair falling once again to cover her face. He didn’t sense fear from her. No, he sensed frustration. She took a breath and let it out like a filly settling to the chafe of bridle and cinch.

“Don’t worry yourself, Miss Small,” Cedar said. “You’re safer here in your home than if you hid away in the blacksmith’s pocket.” He lowered his voice to a conspiratorial whisper. “I’m of a positive considerance not even the bravest bogeyman would dare cross the temper of your mother.”

That tipped a laugh out of her, sweeter than the top’s song, and Cedar couldn’t help but smile in response. There was something about Rose that made a man want to smile.

“You have a way with words, Mr. Hunt. I best be going before that temper is aimed my direction.” She started across the porch and opened the door just as her mother yelled for her.

“Rose, get the broom and pan. And I’ll have you fetch the papers from city hall before the day’s gone dead. The rail man’s expecting them tomorrow. Are you listening to me? Rose!”

“Coming, ma’am,” she called back.

Cedar watched her step through the doorway, caught for a moment as a lithe silhouette between the light and darkness, a graceful girl—no, he reckoned she really was a woman now—who paused just long enough to glance over her shoulder at him, and give him a curious smile.

Then the Madder brothers came walking out, each calling a hello to Rose, and each fixing Cedar with a hard look.

Cedar got moving, down the steps and out into the busy street. He’d come to town on foot, wanting the walk. But he didn’t want to deal with the brothers. Not today.

A cool breeze pulled down off the mountains and pushed a few clouds across the sky. Signs that summer’s back would soon be broken by frost.

No time left to plant, to harvest, to spend the days hopeful and hale. The season of the dead was coming round the way. Maybe the storekeeper’s wife was right. Maybe it was time for moving on to better hunting grounds before winter took hold. Maybe it was time to run again.

Cedar could feel the restlessness in the little Oregon town. Everyone twitching for a bit of sunlight that gave off enough warmth to last a day. Twitching for moving on, moving up to a better place in the modern world, to a better bit of luck. Before winter caught hold and locked the town tight between the feet of the Wallowa and Blue mountains.

The people of Hallelujah had been holding out against hard times for too long now. Killing winters, broken supply trains and routes, sickness. They hung their hopes like threadbare linens on the iron track that was laying down, tie by tie, coming their way with the promise of a new tomorrow and all the riches of the east and south.

No wonder they bowed to the rail man. He was all they had left to hope for.

Cedar strolled down the street, dodging a slow horse and a passel of kids chasing after a pig that must have gotten loose from its pen. The dirt under his bootheels was still hard from a season of sun, and he made good time crossing one street, then another.

Didn’t matter how busy town was today. The Madder brothers followed him like a pack of dogs scenting meat.

He stopped at the end of the street. The western edge of forest crowded up here, making homesteading more difficult. His cabin was about three miles into those trees, up the foothills a bit, by a creek that flowed through the seasons. If the Madders had some business with him, he’d rather deal with it here than at his home.

He didn’t want a fight, and he didn’t want to draw his gun. But he’d do both to keep the brothers off his heels tonight.

“There something on your mind, boys?”

The middle brother’s name was Bryn. Cedar could pick him out of the pack because he was always covered in dirt and grime from the mine—except for his hands, which he kept scrubbed from the wrist to fingertips, clean as a preacher’s sheets. He stepped forward.

“We think maybe you lost something.” He stuffed one of his clean, calloused hands into his overalls pocket and drew out a pocket watch. He gazed down at it longingly until the oldest, tallest, Alun, said, “Go on now, Bryn. Make it right.”

Bryn Madder looked away from the watch and held it out for Cedar. “It’s yours. As much as. I . . . found it. A while back. Broken. I cleaned it. Didn’t fix it, though. Wouldn’t take to fixing, and that’s a curious thing.”

The watch swung like a pendulum, stirred by the breeze: a silver disk, an accusing eye, cold and hard as hatred.

“A lot of men carry a watch.” Cedar’s throat felt like he’d just swallowed down ashes of the dead. That watch was not his. But he would know it anywhere. It was his brother’s. And he’d last seen it on him the day he died.

Bryn nodded. Tilted his chin so he could look at Cedar through his good left eye. “This one you lost. We found it. Maybe eight months ago when that rail man dandy came to town. Thought about keeping it . . .” His voice trailed off on a note of longing.

“But it’s not the sort of thing we’d need,” Alun said, more for his brother than Cedar. “Now, if it had been something useful to us, like say that striker we’ve seen you carry a time or two . . .”

“Is that what you want for it?” Cedar could not look away from the watch, gently swaying like an admonishing finger.

The brothers paused.

Cedar glanced at the oldest, Alun, who wore a heavier beard than the rest. “How much?”

Alun did not look away. Instead, he did something very few could do beneath Cedar’s glare. He smiled.

“Our blood comes from the old country, Mr. Hunt,” he said. “Before Wales had that name. And our . . . people . . . have always been miners. A man sleeps and breathes and sups with the stone, he begins to understand things.”

A wagon pulled by mule, not steamer, rattled past, taking crates and sacks and barrels of food, nails, mended shovels, and hammers out to the rail work twenty miles south of town.

“All things in this world eventually soak into the soil and stone,” Alun said once the wagon had taken its noise up the street a ways.

“It gets to be where a man, one who knows what to listen for, can hear the stones breathing. It gets to be where a man knows what the stones have to say.”

“The watch.” Cedar didn’t care if Alun thought he could hear rocks conversing. Hell, for all Cedar knew, he was telling true and he could talk to stones. The brothers had strolled into town a year ago, just ahead of the rail man, and quickly struck the richest silver vein in the hills. Maybe they’d gone out and asked the mountain where the metals were hid.

And maybe the mountain had sat down and told them.

Talking to rocks wasn’t near the strangest thing Cedar had encountered on his walk across this country. He had seen the Strange—the true Strange—creatures that hitched along from the Old World, tucked unknown in an immigrant’s pocket, hidden away in a suitcase, or carried tightly in the darkest nightmare. He had seen what the Strange could do when set free in this new land. He had seen it more clearly than someone fixing to blame the bogeyman for a missing child. He had seen the Strange personally, been touched by them.

And he still hadn’t recovered.

It looked like the Madder brothers’ Strange had done them benefit. They were wealthy by any man’s standard, even though they never spent much, never left the hills much, and lived like they didn’t have a penny between them.

They had a way with metal, that was sure. It showed in their buckles and buttons, each carved with a symbol of a gear and wrench, flame and water. It showed in the glimpses of brass and copper contraptions that rode heavy in the pockets of their oversized coats.

And it showed in the customized Colt pneumatic revolvers glinting in handworked silver and brass, holstered at their hips.

He was of a mind they were also devisers, though they’d never come out and said such. Made him curious why they didn’t want to admit to their skill. A deviser could make things of practical applications that stretched the imagination. Yet folk in town always turned them a blind eye, while looking instead with hope to the rail man, LeFel.

“The watch isn’t yours, is it?” Alun Madder said. “Stones say this belonged to someone close to you. Someone gone. A brother?”

Cedar held out his hand for the watch. “Those stones of yours talk too much.”

That got a hoot out of all three of them.

“What is your asking price for the watch?” Cedar said.

“The striker. And a favor.”

“What favor?”

The Madder brothers all shrugged at the same time. “Don’t know,” Alun said. “Don’t need a favor yet. But when we do, you’ll answer to us and pay it.”

Cedar paused. He didn’t like being left owing to any man, much less three. But that was Wil’s watch. Rightfully his now. He wanted it. More, he wanted to know how it had suddenly appeared, all the way out here, almost four years after his death.

“One favor only,” Cedar said, “not one for the each of you. I’ll do nothing that brings harm to the weak, the poor, or to women and children.”

“Yes, yes.” Alun rubbed his meaty hands together. “And the striker.”

“You’ll have it next time I’m in town.”

“Agreed,” Alun said.

The Madder brothers leaned in and extended their right hands as one, palms pressed against knuckles so they all shook Cedar’s hand at the same time. Practiced, unconscious—they’d probably been sealing deals that way since they could talk.

Cedar held his hand out for the watch again. Bryn released the chain and sighed as the watch slipped his fingers into Cedar’s.

It should be cold, made of silver and brass with a crystal face. But the watch was as warm as if there were a banked coal tucked inside. It didn’t tick, not even the second hand. It was still, dead. And warm as a living thing.

Dead Iron- Excerpt

Not too long ago, I announced we had a few advanced review copies of DEAD IRON available for review. Those are all gone now, and I’m seeing a few reports that the copies have arrived safely in the hands of reviewers. (yay!)

But hey, not everyone reviews books. Some of us just read the things.

So I thought readers might like a nice, juicy excerpt of the first chapter of DEAD IRON. I’ll be posting more snippets of the book as we get closer to the actual release day (July 5th) so stay tuned. But for now I give you, Dead Iron:

*******************

DEAD IRON

Chapter One

Cedar had stared straight into the killing eyes of rabid wolves, hungry bears, and charging bull elk, but Mrs. Horace Small had them all topped.

With dirt brown hair piled in a messy bun on the back of her head, and a pinch of anger between her brows, the storekeeper’s wife always seemed half a tick from blowing a spring.

“Two dollars,” she repeated, her fist stuck wrist-deep in the fabric at her hip, her jaw jutted out like a bass on a hook.

“Cornmeal, coffee, and a bit of cheese,” Cedar said mildly. He knew better than to let his anger show, especially this close to the full moon, in a store full of townsfolk eager to get their hands on the fresh supplies and gears from the old states. “Might be I’m missing something.” He looked back down at the receipt with Mrs. Small’s tight penmanship. “How again do they add to two dollars?”

He knew math—knew it very well. He’d spent four years back east in the universities and had plans of a teaching life. History and the gentle arts, not the wild metal and steam sciences of the devisers. He’d done his share of tinkering—had a knack for it—but not the restless drive of a true deviser who couldn’t be left in a room with a bit of rope, metal, and a hammer without putting them all together into some kind of engine or contraption.

No, his needs had been simple: a teacher’s life filled with a wife and a daughter, and his brother, Wil. But that life had been emptied out and scraped clean six years ago, when he’d been only twenty-two. Leaving him a changed man.

Leaving him a cursed man.

“It’s written plain enough,” she said. “You do read, Mr. Hunt?”

“The part there that says ‘fee,’” Cedar asked without looking up. “What fee is that?”

“The rail takes its due. You aren’t part of the railroad, Mr. Hunt. Not a farmer, miner, rancher, or deviser. Not a member of this good community. I’ve never seen you in church. Not one single Sunday the last two years. That fee for the rail is less than all those months’ dues you owe to God.”

“Didn’t know the collection plate took hold to my provisions,” he said with a little more irritation than he’d intended, “and I don’t recall offering my wages to the rail.”

The mood in the general store shifted. The men in the shop—the three Madder brothers, dark haired, dark eyed, all of them short, bull-shouldered, and strong—were listening in. They’d stopped pawing and chuckling at the new metals and bits in the straw-padded crates, and were waiting. Waiting for him to say the wrong thing. Waiting for a fight.

Rose, Mrs. Small’s seventeen-year-old adopted daughter, stepped down off the stool where she’d been dusting. She darted behind Cedar and out the door, silent as a mouse fleeing danger. She had good instincts. He’d always admired that in her.

Mrs. Small lowered her voice and leaned over the counter between them. “You are a dirty drifter, Mr. Hunt. Any man out this far west with no plan of settling down isn’t drifting toward something—he’s trying too hard to drift away from something. The good folk of this town want you to be moving on. You’ve brought enough bad luck down on us. First the Haney stock got drug away by wolves. Then the little Gregor boy goes missing. Trouble like you needs to be moving on your way.”

“Trouble like me?” He tipped his hat down just a bit. “No offense, ma’am, but I took care of the wolf before the Haneys lost the rest of their stock. If I recall, there wasn’t another man out tracking it. And if I’d known about the Gregor boy wandering off, I would have been looking for him too. Animals aren’t the only thing I am capable of hunting.”

This time he did look up. Met her eyes. Watched the fire of her indignation go to ash. It never took much, no more than a glimpse of the thing that lived just beneath his civilized exterior, to end a conversation.

Days like this, he liked it. Liked what his gaze could do. But it was easy to lose grip, to go from staring a person down to waking up with a dead body at his feet. He didn’t want that to happen. Not today.

Not ever again.

Cedar blinked, breaking eye contact with Mrs. Small. He pushed the bloody memories away and gave her a moment, because he knew she’d need one.

He took a moment too. He meant it when he said he’d look for the boy, would have been looking at the first sign of him getting lost. But Hallelujah wasn’t made of trusting folk. They’d seen too much hardship to think a man who kept to himself, and only rarely came to town, would go out of his way to do them any good.

Except for the dandy rail man, Mr. Shard LeFel. Rumor had it all the town held him in high esteem. Rumor had it, when he or his man Mr. Shunt walked by, folk fought a powerful need to bow down on their knees.

Cedar hadn’t yet met a man he’d be willing to bow to.

The Madder brothers swaggered up, caulk boots hollow on the shiplap floor. The brothers worked the silver mine. Breaking rock all day never seemed to satisfy their need to bust their way through a man’s bones every time they crawled out of the hills.

“How I see it,” Cedar said, hitching his words down low, quiet, “I’ve been some benefit to this town, me and my drifter ways. Hunted wolves, mountain lions, and nuisances for ranchers and working folk alike. I’ll be hunting for the lost boy. You can tell the Gregors that when they next stop in.”

He dug in his pocket and pulled out a silver dollar and enough copper to settle the bill. Fee included. He placed the coins on the counter, plus a penny extra, and plucked a jar of ink from the shelf.

Mrs. Small raised one eyebrow, but said no more.

The silver filigreed bird perched on the edge of the high window sang one sweet chirp. Its head was the size of a child’s thimble. The gears and burner inside it were so tiny, it chirped once every hour and needed half a dropper of water a day to power it.

Valuable, that whimsy. He wondered where she had come by it. That delicate of a matic, a fine thing of little practical use, never survived this far west for long.

Beautiful things got crushed to dust out in these wilds.

Outside, the steam clock blew the pattern for ten o’clock. Town was mighty proud of that whistle. The blacksmith, Mr. Gregor, had put it in place of a clock tower right over his shop at the north end of town. Not half again as nice as the steam bells back east, it was still Hallelujah’s pride and joy and could be heard clear on the other side of Powder Keg Bluff.

“Is Mr. Hunt troubling you, ma’am?” Cadoc, the shortest and widest of the Madder brothers, asked.

Cedar picked up the flour with the two smaller bundles stacked on top. He tucked the ink in his pocket and nodded at the brothers, who all wore overalls, tool belts, and long coats loose enough to cover whatever it was they kept stuffed in their pockets. “Just a discussion of good citizenship is all, gentlemen,” he said. “Afternoon.”

He headed out onto the stretch of porch that gave shade in the summer, and the chance of shelter against rain and snow in the other seasons.

The Small Mercantile and Groceries was set on the corner of Main Street—the only street with real gas lamps in the town. The other buildings, thirty or so of them with pitched roofs and walls of milled or plank wood, were laid out in neat rows following the curve of the Grande Ronde River north.

A bustle of people were on the streets this morning, come into town for the new shipment, to pick up mail or trade harvest goods to settle their bills. It brought back his memories of the big cities, though there were more steam matics trundling about in the East. Horses, carriages, wagons, and folk on foot added to the clatter of the place, added to the living of the place, and reminded Cedar of things long lost.

Even the ringing of a hammer on wood reminded him of the civilized life that was once his.

He glanced up the street. His gaze skipped the bakery, butcher shop, tannery, and mill, drawn, as it was always drawn, to the clock whistle atop a turret made of iron and wood and tin, sticking up like a backbone above the blacksmith’s shop. A coil of copper tubes wrapped through the structure and supported a line of twelve glass jugs, round as pearls and big as butter churns. Water poured from the top of the tower downward, like sand in an hourglass, filled the glass jugs one at a time, until they spilled over into the next and turned the gears inside the tower toward the next hour.

Town needed a thing to be proud of. Needed a thing more than wool and timber and silver to keep it alive. Needed something beautiful. Needed hope.

Cedar looked past the tower to the mountains that cupped the valley, two ranges of snow and hardship, blocking Hallelujah from easier lands and the great Columbia River. He knew there was ground enough between the town and the rise of the Wallowa Mountains, an airship could land and lash, but he had never once seen a ship venture over these mountain ranges—not even to deliver supplies or drop mail.

Hallelujah was in dire risk of being forgotten by the world that traveled easier roads to brighter skies.

A song piped out from near his elbow, soft and breathy. Cedar looked down.

Rose was on the porch, her back pressed tight against the clapboard siding, one toe of her boot propped on the lower rung of the whitewashed railing. She was talking to herself, or maybe singing, her head bent, amber hair beneath her bonnet catching the gold out of the sunlight and falling in a loose braid over one shoulder, hiding much of her profile from him.

Around her neck was a little locket the size and shape of a robin’s egg. It looked made of gold and silver, though it might just be the shine of the morning sun upon it. He’d never seen her without that locket around her neck.

She balanced a small wooden plate with gears set flat atop it on the palm and fingers of her left hand. A tiny tin top with a copper steam valve followed the spokes of the wooden gears and gave off a sour little song that changed with its speed as it followed the height and width of each cog. Rose pulled a gear off the plate and replaced it with another from her apron pocket, sweetening the song, all the while talking, talking.

Clever, that.

He’d bet she fashioned it herself. She had the look of the deviser’s knack—a quick mind that trawled the edge of madness, and clever, busy fingers. She had practical smarts too, though, like knowing how to stay away from the back of her mama’s hand.

“Reckon I put your mama in a sour mood, asking her about the Gregor boy,” he said. “I don’t suppose you’ve heard when he got himself lost?”

“Last night is all,” she said, stopping the top with her finger and slipping it into her apron pocket. “Didn’t run off, I heard.”

“Didn’t run? Think he flew out the window?”

She tipped a glance out from behind the brim of her bonnet. Those eyes were blue and soft and wide as the sea. She smiled, the corners of her mouth tucking dimples into her tanned cheeks. Folk around town had their opinions of the girl abandoned when she was a babe. Thought she had too many wild ideas spinning through her head as was proper for a woman. He’d never seen her be anything but kind and steady in the years he’d been here. Deviser or not, madness or not, she had a good heart, that was certain.

Didn’t seem the other men in town thought the same. A woman her age and unmarried was almost an unheard-of circumstance.

“No, Mr. Hunt,” she said. “I think he got took.”

“Took? That what his folks are saying?”

She shrugged.

“They saying what took him?” There wasn’t a night predator brash enough to cross a closed door, and there wasn’t a soul foolish enough to go without a lock or brace in these parts. Maybe the boy wandered when he should have been sleeping.

“Said it was the man.”

“What man?”

“The bogeyman.”

Cedar blinked and went very still. She wasn’t lying. That was clear from the curiosity in her eyes. She’d heard someone say that, someone who meant it. He just hoped whoever had said it didn’t know what they were talking about.

Under his sudden silence, Rose clutched the wooden gear plate tighter and pulled her braid back so it fell square between her shoulders. She did not look away, but lifted her chin and studied his face, his eyes, the angle of his shoulders, his clenched fists. She weighed and measured his mood as if he were made of parts and the whole, more curious than cautious, though she rocked up on the balls of her feet, ready to bolt if need be.

And for good reason. He’d been staring at her. He knew what she saw in his gaze. Knew the beast that twisted inside him. He looked away.

“Mr. Hunt?” she asked. “Are you not well?”

Like he said, she had good instincts. Cedar found a smile and gentle tone left over from better days.

“Well enough. Thank you for your time, Miss Small.”

“Do you think it was?” she asked. “The bogeyman?”

“I think a lady like you shouldn’t need to fret about the bogeyman.”

She did not smile. “They say he came in the night,” she said. “Slick as a shadow. Took Elbert from his bed. Didn’t even leave a wrinkle in the sheets. No one saw him. No one heard him. No one stopped him. Not even his daddy. It’s unnatural.” She nodded and looked him straight in the eyes. “Strange. I think that might be worth a fret or two, don’t you?”

Mr. Gregor was a big man. A strong man with hair and beard as red and wild as the fire he toiled over. Probably looked like a giant from the eyes of a girl growing up in this town.

A crash from inside clattered out; then Mrs. Small’s holler drifted through the doors. Rose flinched, tucked back down into herself, her hair falling once again to cover her face. He didn’t sense fear from her. No, he sensed frustration. She took a breath and let it out like a filly settling to the chafe of bridle and cinch.

“Don’t worry yourself, Miss Small,” Cedar said. “You’re safer here in your home than if you hid away in the blacksmith’s pocket.” He lowered his voice to a conspiratorial whisper. “I’m of a positive considerance not even the bravest bogeyman would dare cross the temper of your mother.”

That tipped a laugh out of her, sweeter than the top’s song, and Cedar couldn’t help but smile in response. There was something about Rose that made a man want to smile.

“You have a way with words, Mr. Hunt. I best be going before that temper is aimed my direction.” She started across the porch and opened the door just as her mother yelled for her.

“Rose, get the broom and pan. And I’ll have you fetch the papers from city hall before the day’s gone dead. The rail man’s expecting them tomorrow. Are you listening to me? Rose!”

“Coming, ma’am,” she called back.

Cedar watched her step through the doorway, caught for a moment as a lithe silhouette between the light and darkness, a graceful girl—no, he reckoned she really was a woman now—who paused just long enough to glance over her shoulder at him, and give him a curious smile.

Then the Madder brothers came walking out, each calling a hello to Rose, and each fixing Cedar with a hard look.

Cedar got moving, down the steps and out into the busy street. He’d come to town on foot, wanting the walk. But he didn’t want to deal with the brothers. Not today.

A cool breeze pulled down off the mountains and pushed a few clouds across the sky. Signs that summer’s back would soon be broken by frost.

No time left to plant, to harvest, to spend the days hopeful and hale. The season of the dead was coming round the way. Maybe the storekeeper’s wife was right. Maybe it was time for moving on to better hunting grounds before winter took hold. Maybe it was time to run again.

Cedar could feel the restlessness in the little Oregon town. Everyone twitching for a bit of sunlight that gave off enough warmth to last a day. Twitching for moving on, moving up to a better place in the modern world, to a better bit of luck. Before winter caught hold and locked the town tight between the feet of the Wallowa and Blue mountains.

The people of Hallelujah had been holding out against hard times for too long now. Killing winters, broken supply trains and routes, sickness. They hung their hopes like threadbare linens on the iron track that was laying down, tie by tie, coming their way with the promise of a new tomorrow and all the riches of the east and south.

No wonder they bowed to the rail man. He was all they had left to hope for.

Cedar strolled down the street, dodging a slow horse and a passel of kids chasing after a pig that must have gotten loose from its pen. The dirt under his bootheels was still hard from a season of sun, and he made good time crossing one street, then another.

Didn’t matter how busy town was today. The Madder brothers followed him like a pack of dogs scenting meat.

He stopped at the end of the street. The western edge of forest crowded up here, making homesteading more difficult. His cabin was about three miles into those trees, up the foothills a bit, by a creek that flowed through the seasons. If the Madders had some business with him, he’d rather deal with it here than at his home.

He didn’t want a fight, and he didn’t want to draw his gun. But he’d do both to keep the brothers off his heels tonight.

“There something on your mind, boys?”

The middle brother’s name was Bryn. Cedar could pick him out of the pack because he was always covered in dirt and grime from the mine—except for his hands, which he kept scrubbed from the wrist to fingertips, clean as a preacher’s sheets. He stepped forward.

“We think maybe you lost something.” He stuffed one of his clean, calloused hands into his overalls pocket and drew out a pocket watch. He gazed down at it longingly until the oldest, tallest, Alun, said, “Go on now, Bryn. Make it right.”

Bryn Madder looked away from the watch and held it out for Cedar. “It’s yours. As much as. I . . . found it. A while back. Broken. I cleaned it. Didn’t fix it, though. Wouldn’t take to fixing, and that’s a curious thing.”

The watch swung like a pendulum, stirred by the breeze: a silver disk, an accusing eye, cold and hard as hatred.

“A lot of men carry a watch.” Cedar’s throat felt like he’d just swallowed down ashes of the dead. That watch was not his. But he would know it anywhere. It was his brother’s. And he’d last seen it on him the day he died.

Bryn nodded. Tilted his chin so he could look at Cedar through his good left eye. “This one you lost. We found it. Maybe eight months ago when that rail man dandy came to town. Thought about keeping it . . .” His voice trailed off on a note of longing.

“But it’s not the sort of thing we’d need,” Alun said, more for his brother than Cedar. “Now, if it had been something useful to us, like say that striker we’ve seen you carry a time or two . . .”

“Is that what you want for it?” Cedar could not look away from the watch, gently swaying like an admonishing finger.

The brothers paused.

Cedar glanced at the oldest, Alun, who wore a heavier beard than the rest. “How much?”

Alun did not look away. Instead, he did something very few could do beneath Cedar’s glare. He smiled.

“Our blood comes from the old country, Mr. Hunt,” he said. “Before Wales had that name. And our . . . people . . . have always been miners. A man sleeps and breathes and sups with the stone, he begins to understand things.”

A wagon pulled by mule, not steamer, rattled past, taking crates and sacks and barrels of food, nails, mended shovels, and hammers out to the rail work twenty miles south of town.

“All things in this world eventually soak into the soil and stone,” Alun said once the wagon had taken its noise up the street a ways.

“It gets to be where a man, one who knows what to listen for, can hear the stones breathing. It gets to be where a man knows what the stones have to say.”

“The watch.” Cedar didn’t care if Alun thought he could hear rocks conversing. Hell, for all Cedar knew, he was telling true and he could talk to stones. The brothers had strolled into town a year ago, just ahead of the rail man, and quickly struck the richest silver vein in the hills. Maybe they’d gone out and asked the mountain where the metals were hid.

And maybe the mountain had sat down and told them.

Talking to rocks wasn’t near the strangest thing Cedar had encountered on his walk across this country. He had seen the Strange—the true Strange—creatures that hitched along from the Old World, tucked unknown in an immigrant’s pocket, hidden away in a suitcase, or carried tightly in the darkest nightmare. He had seen what the Strange could do when set free in this new land. He had seen it more clearly than someone fixing to blame the bogeyman for a missing child. He had seen the Strange personally, been touched by them.

And he still hadn’t recovered.

It looked like the Madder brothers’ Strange had done them benefit. They were wealthy by any man’s standard, even though they never spent much, never left the hills much, and lived like they didn’t have a penny between them.

They had a way with metal, that was sure. It showed in their buckles and buttons, each carved with a symbol of a gear and wrench, flame and water. It showed in the glimpses of brass and copper contraptions that rode heavy in the pockets of their oversized coats.

And it showed in the customized Colt pneumatic revolvers glinting in handworked silver and brass, holstered at their hips.

He was of a mind they were also devisers, though they’d never come out and said such. Made him curious why they didn’t want to admit to their skill. A deviser could make things of practical applications that stretched the imagination. Yet folk in town always turned them a blind eye, while looking instead with hope to the rail man, LeFel.

“The watch isn’t yours, is it?” Alun Madder said. “Stones say this belonged to someone close to you. Someone gone. A brother?”

Cedar held out his hand for the watch. “Those stones of yours talk too much.”

That got a hoot out of all three of them.

“What is your asking price for the watch?” Cedar said.

“The striker. And a favor.”

“What favor?”

The Madder brothers all shrugged at the same time. “Don’t know,” Alun said. “Don’t need a favor yet. But when we do, you’ll answer to us and pay it.”

Cedar paused. He didn’t like being left owing to any man, much less three. But that was Wil’s watch. Rightfully his now. He wanted it. More, he wanted to know how it had suddenly appeared, all the way out here, almost four years after his death.

“One favor only,” Cedar said, “not one for the each of you. I’ll do nothing that brings harm to the weak, the poor, or to women and children.”

“Yes, yes.” Alun rubbed his meaty hands together. “And the striker.”

“You’ll have it next time I’m in town.”

“Agreed,” Alun said.

The Madder brothers leaned in and extended their right hands as one, palms pressed against knuckles so they all shook Cedar’s hand at the same time. Practiced, unconscious—they’d probably been sealing deals that way since they could talk.

Cedar held his hand out for the watch again. Bryn released the chain and sighed as the watch slipped his fingers into Cedar’s.

It should be cold, made of silver and brass with a crystal face. But the watch was as warm as if there were a banked coal tucked inside. It didn’t tick, not even the second hand. It was still, dead. And warm as a living thing.

3 Comments

Pingback:

Maithe

Oh, this is good–caught my interest! I tend to avoid steampunk stories, but I like this one. *G*

kindle-aholic

Looking forward to this one…Thanks for the snippet!